Born in 1887, Ukrainian-born artist Alexander ‘Sacha’ Zaliouk eventually settled in Paris. It was there that he established himself among the artists of the interwar period (1918 – 1939) through his contribution to several magazines, including La Vie Parisienne and Le Sourire. Sacha also participated in artistic groups, most notably the group known as La Horde de Montparnasse.

Sacha’s art was placed in exhibitions alongside artists such as Tsuguharu Foujita. He attended dinners with the likes of André Salmon and Marie Wassilieff, and frequented cafés like La Rotonde, which also welcomed Pablo Picasso, Moïse Kisling, and Amedeo Modigliani, among numerous others. He was apparently well-acquainted with Jean Metzinger.

While these artists have been remembered through several articles, books and exhibitions, Sacha has remained almost entirely forgotten, especially in academia. In the art world, his sculptures, portraits and paintings are circulated on a regular basis, often accompanied by biographical information which contradicts archival evidence.

This blog intends to document all and any information relating to Sacha Zaliouk which might offer a clearer depiction of his life and artistic impact. To do so, portions of Zaliouk’s life will be examined alongside this forementioned archival evidence as well as any newspaper clippings or other relevant documentation from the time period.

Sacha deserves to be remembered as much as any other artist. Even if only a patchwork image can be captured of what Sacha achieved in his lifetime, it will allow his memory to continue, and potentially for others interested in this time period to learn of his impact.

Montparnasse: Context and Culture

To flesh out the period in which Sacha lived, it’s beneficial to describe Montparnasse and its artists during his lifetime. During La Belle Époque in France, Montmartre was the creative hub of Paris where artists flourished; where Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec painted and Rodolphe Salis crafted the famous Chat Noir (Bertrand, 2021). It then transitioned to Montparnasse, but Montmartre’s influence is still significant to note here.

While Émile-Bayard lists many cafés of the era in his book, Montparnasse Hier et Aujourd’hui, perhaps the three most famous are: Le Dôme, La Rotonde, and La Coupole. Victor Libion owned and ran La Rotonde from 1911, and Libion’s generosity toward poor artists is considerable (Nieszawer and Princ, 2020).

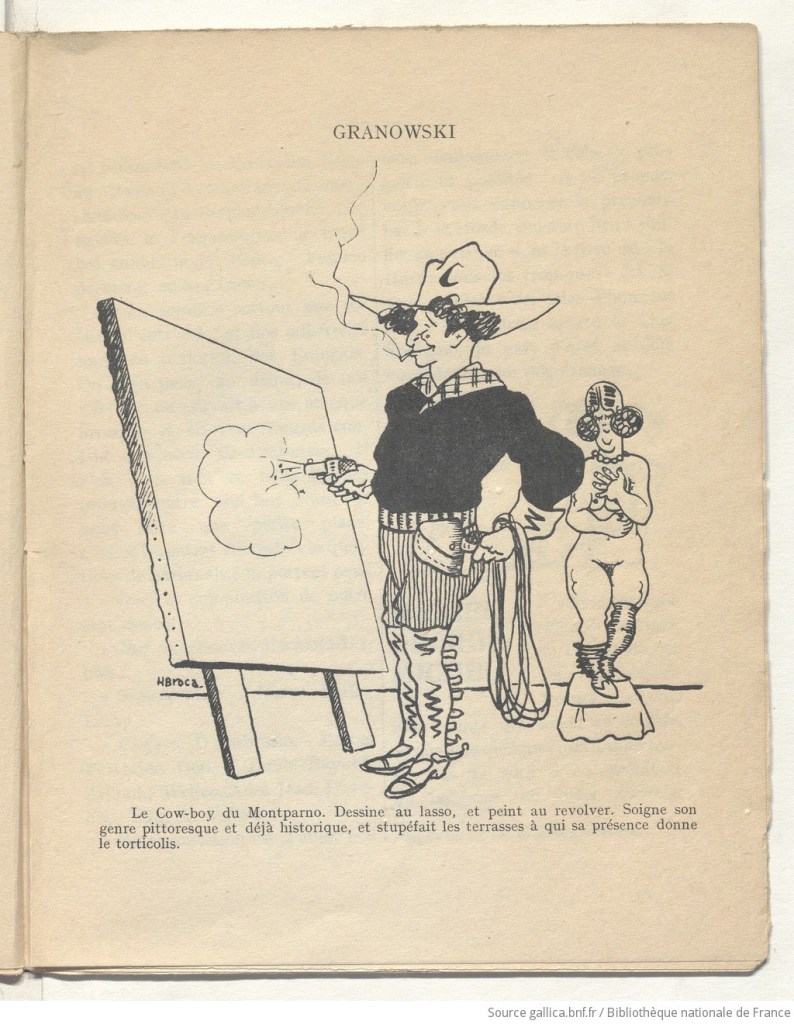

Henri Broca, an artist of Sacha’s time, compiled some contemporary opinions of Montparnasse in his book, T’en fais pas, viens à Montparnasse ! enquête sur le Montparnasse actuel. It plunges the reader into the ‘characters’ of this quartier – ‘le cow-boy Granowski’, referring to Samuel Granowsky (1882-1942), and Kiki de Montparnasse, the famed model (1901-1953). Granowsky, famous in this quartier for his originality and his relationship with the model Aïcha, was later murdered in Auschwitz, (Nieszawer and Princ, 2020, p.162).

Broca carries the reader through the cafés noted above, further noting the presence of Tsuguharu Foujita (1886-1968) at La Coupole, and the sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1888-1967). He includes many artists such as Pol Rab (1898-1933) who created the newspaper Ric et Rac.

On page 12, Broca mentions Fernand-Dubois, the founder of the artistic group La Horde du Montparnasse, of which Sacha was a member. On page 48, Dubois describes La Horde, and says it has 800 members (who pay for membership), breaks down their earnings, and notes that their aim is to help their unfortunate friends. He also mentions the ‘bal de la Horde’, the ball thrown by the group, which ‘will take place at Bullier in April’, and whose title is ‘La Horde under the tropics’. We can see an example of a party held by La Horde in this video from 1932. Dubois counts Sacha among the members of the group under ‘Leaders’.

Dubois’ Wikipedia notes that he died ‘poor and forgotten’, but he was a presence in Montparnasse like all the others.

Broca goes into great detail about this ‘Bal sous les Tropiques’ hosted by La Horde. It is, according to Broca, highly-anticipated, with nude dancers and a wonderful atmosphere. Broca adds a line about Sacha on page 73: “Charles Lagrille félicite le décorateur Zaliouk (Charles Lagrille congratulates the decorator Zaliouk.)”

Broca’s collection of mini ‘interviews’ could be snippets from other publications, given the quotations used by Granowsky are also repeated in Émile-Bayard’s book on page 497: “Je suis le premier client de la Rotonde, ça remonte à 1906. Mais Montparnasse a bien changé ! C’est une très bonne choise que la Foire aux Navets* ; les marchands ont protesté ! Ça ne fait rien ! On vend pas mal, vous savez ! Si vous voulez, dites donc qu’il y a ici beaucoup trop de profiteurs et de tapeurs, pas artistes du tout.“

Translation: “I am the first customer of the Rotonde, it dates back to 1906. But Montparnasse has changed a lot! La Foire aux Navets (lit: the Turnip Fair)* is a very good thing; the merchants protested! That did nothing! We sell quite a bit, you know! If you want, say that there are far too many profiteers and thugs here, not artists at all.”

*La Foire aux Navets refers to the flea market events organised by La Horde.

In addition, the writer Chil Aronson wrote the following about Granowksy in a book that has not yet been fully translated from Yiddish into English, but of which a portion has been posted online:

“In the Rotonde I became acquainted with the painter Granovsky, known as “the cowboy.” He was one of the artists who had come from Eastern Europe before the First World War. In 1914 he had enlisted in the Foreign Legion and distinguished himself on the battlefield. When I think of him now, I see him in his cowboy uniform, with a wide hat and a checkered shirt. Always smiling, always optimistic, he looked like an old-fashioned Jewish tradesman. I never found out why he dressed like a cowboy. He was one of the most popular figures in Montparnasse, but he rarely sold a painting. In order to earn a living, he worked as a house-painter. He’d greet me warmly from across the room. “Bonjour, Aron! Ca va?”

During the German occupation, he was taken from his home and deported. Perhaps he thought that Pétain’s mob would treat him well because he had fought at the front on behalf of France. My memories of La Rotonde are always bound up with Granovsky, the vanished cowboy.”

How well Sacha knew other artists of this time, is not always easy to say. It is said online that he was deeply affected by Granowsky’s death, and I can’t imagine that it would be untrue given the circumstances.

Sacha appears in articles with Jean Metzinger, (example from 1924, and the image also from 1924, and see ‘Mentions of Sacha in the Media’ for more). He exhibits his art alongside Foujita and other artists at La Rotonde (1923), and there is a portrait shown on an art gallery site which reports Sacha sketched a portrait of Foujita and it is signed by both Foujita and Sacha.

We know Sacha attended many parties of La Horde, and we see how he dressed up for them in articles such as this one (1928) where he ‘led La Horde’ in the costume of Lucifer. Also in 1928, he attended a charity event and was recognised alongside Marie Wassilieff (also spelled Vassilieff, the painter and set designer), and Foujita’s wife.

While it is not possible to definitively connect Sacha and other artists in every case, it is obvious he was deeply embedded in the artistic life of Montparnasse and contributed to it immensely. His Montparnasse was that of creativity and different cultures blending together, of parties, of intellectual conversation, and more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.